Monday, April 1, 2024

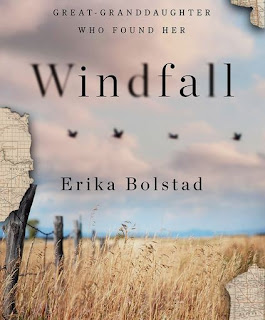

Windfall, by Erika Bolstad: Tragic, disheartening, and encouraging

Monday, June 4, 2012

Coyotes, Carbon, and Corn

My aunt, who I was staying with while I pulled weeds in the woods, had more information that evening. She said the coyotes had been leaving the woods and going over to the neighbors’ house. They shot the animals to keep them out of their yard. I remembered that dogs had barked at me from across the road when I popped out of the woods on that side. Once I knew about the neighbors’ dogs, I knew what the coyotes were eating. They weren’t finding it in our woods.

I understood what was happening in Indiana because I missed a question in a graduate student exam at the University of Arizona. One of my professors asked if coyotes on the east side of Tucson were eating plants--and animals that ate plants--that grew in winter or in summer.

His exact words were, "What’s the carbon isotope ratio of coyotes on the east side of Tucson?”

Isotopes are different versions of elements; carbon is one of the elements. All plants use carbon, from the carbon dioxide (CO2) in the air, to make food and grow. Plants get CO2 through pores, or stomates, in their leaves. However, there’s a danger to opening these structures to let in CO2. Whenever their stomates are open, plants are also losing water through evaporation--the plants are drying out.

Plants that grow during Tucson’s hot summers use CO2 more efficiently than plants that grow during the cool winters. Summer plants are more efficient because they use more of each batch of CO2 they bring in, right down to the dregs. For plants, the dregs are CO2 molecules that contain the carbon isotope they don’t like as well.

This means that summer-growing plants use more of the less preferred isotope than winter-growing plants. When scientists compare the amounts of the two main isotopes of carbon, they can tell if an animal has been eating plants, or animals that ate plants, that grew in the winter or the summer.

When I answered the question, I guessed that the coyotes and their prey were eating whatever was in season. They both had to make do with what they could find among the tall saguaro cactus and shrubby triangle leaf bursage of the Sonoran Desert that surrounds Tucson.

What I didn’t know was that the Tucson coyotes were leaving the desert and coming into town--just as the Indiana coyotes had been leaving our woods and going to the neighbors’ place.

The professor said that the coyotes were eating summer plants all year. Make that one summer plant: corn. The coyotes were coming into town to clean up dog food left in back yard bowls. Most of the major dog food brands are mainly corn, so the coyotes were living on corn kibble.

Our Indiana neighbor's dog food bowl was a more reliable source of food than the few prey animals in our woods. And the dog food was a lot easier to sneak up on. I wondered if our neighbors knew they were helping the coyotes raise large litters of pups that would then follow their parents to dinner.

I emailed my mother about the coyotes in her woods and the corn kibble at the neighbors’ the next day. She understood the coyote issue because she had seen another example near where she lives. She emailed back that Edina, Minnesota had been "overrun by coyotes" a few of years earlier. "People saw them in the parks, and they attacked small pets," she wrote.

The city thought about trapping the coyotes, but Wile E. Coyote wasn’t just the figment of a cartoonist’s imagination: coyotes are wary and difficult to catch. The city’s legal department said no to killing coyotes in close proximity to taxpayers. Instead, the City of Edina launched an education campaign. Persuading people to stop feeding coyotes either intentionally, in order to watch the animals, or unintentionally, by leaving dog food out, was the safest and most effective way to deal with the problem.

Indiana and Minnesota aren’t the only places where coyotes and people don’t understand each other. The rural-urban interface expands and problems grow as more people bring their urban lives and expectations to rural and wild places. Coyotes are resourceful hunter-gathers. They soon learn that people mean food and poaching dog bowls is an easy living. The people don’t always catch on right away that they’re supporting the local coyote population.

Generations of humans have loved coyotes’ nighttime concerts. The performers are called “song dogs” in southern Arizona. But when people leave bowls of dog food out at night, they’re inviting the band over for an after party. Cutting off the coyotes’ supply of corn kibble is a more effective and more humane way to rescind the invitation than following them to their dens and shooting them.

--------

Update

Edina now encourages residents to haze coyotes.

Monday, April 9, 2012

Carbon Sequestration in Sagebrush Steppe

This grass was able to invade after the native vegetation was killed by the fires that splash blackened smudges across the area most summers. Green for only a few weeks in spring, cheatgrass spends most of its life as a blanket of short, brown stems, leaves, and bristled seeds. The seeds attach to your socks and work their way down into your boots. They use their travelling tricks to spread into other areas where the native plants have been killed or weakened, where they take root.

This grass was able to invade after the native vegetation was killed by the fires that splash blackened smudges across the area most summers. Green for only a few weeks in spring, cheatgrass spends most of its life as a blanket of short, brown stems, leaves, and bristled seeds. The seeds attach to your socks and work their way down into your boots. They use their travelling tricks to spread into other areas where the native plants have been killed or weakened, where they take root.

My friends had lived in Boise long enough that they remembered when the trip east out of Boise was lush with a shrub forest of sagebrush, tall native bunchgrasses, and evanescent wildflowers in spring. The varied plants wove a tapestry of different shades of green that woke up from winter in waves: first the bluegrass, then the squirrel tail, then the needlegrass and wheatgrass filled the areas between the shrubs. The forbs took turns showing off.  Some years the balsamroot astonished my friends with washes of yellow across the hills. Other years the lupines gave it their all and created a pointillist painting with touches of blue. On some trips the red paintbrushes shone and other times it was the yellow ones.

Some years the balsamroot astonished my friends with washes of yellow across the hills. Other years the lupines gave it their all and created a pointillist painting with touches of blue. On some trips the red paintbrushes shone and other times it was the yellow ones.

My friends lived next door to each other and worked together for years; they knew each other's stories. But the sagebrush and grasses and wildflowers spun them a new tale each time they traveled to Mountain Home and beyond.

In addition to entertaining my friends, the native sagebrush vegetation also did a far better job of capturing and sequestering carbon dioxide than the carpet of cheatgrass now does. The Big Ugly contains much less carbon in its soil than it did previously, researchers from Boise State University have found.

You can learn more about the study in a piece I wrote for BSU’s Division of Research and Economic Development.