Bolstad learns more about her family while following North Dakota's oil boom and bust. She weaves her family’s history, and her and her husband’s longing for a child, with her coverage of climate change, fracking, and methane flaring. The interweaving keeps visits with U.S. Geological Survey and university researchers, and oil company employees, from becoming boring, and the personal stories of fertility challenges and multi-generational mental health struggles from becoming (overly) heartbreaking.

Bolstad wonders if her family should profit from an oil boom where workers, chasing windfalls, risk their lives to extract oil that makes billions of dollars for others. She fantasizes about interviewing one of wealthiest oil company owners and asking him, “[W]hen he first understood the world was his for the taking. How did he learn that the rules weren’t for him or anyone like him?...[W]hy he thought he deserved to amass an $11.3 billion fortune when people were living in their cars in a Walmart parking lot, and in church basements and in housing next to his soil field, just so they’d have a crack at a few crumbs of the American dream.”

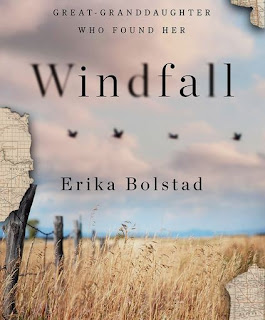

Bolstad makes an admirable and kind decision about her family’s oil lease. The stories she tells in Windfall are, at times, tragic and disheartening, but her response is encouraging.